(2025-05-12) Chin The Heart Of Innovation Why Most Startups Fail

Cedric Chin: The Heart of Innovation: Why Most Startups Fail. Let me tell you a startup horror story. If you’ve been around startups for long enough, you’re likely to recognise this narrative

I want you to imagine that you are a founder of a startup. You make cybersecurity software that detects and blocks botnet attacks. This is 2006, so you are very early to this market — so early, in fact, that the name ‘botnet’ isn’t actually a thing yet. Nobody knows what to call them, so your lab mates call this threat pattern ‘bot armies’.

The lab has developed some cutting edge technology to deal with botnets, and you think you might be on to something big. One day, you show it to the Chief Information Security Officer of eBay, a multi-billion dollar company, and he asks you to come to their offices for a presentation. You do so. eBay’s security team does some back of the envelope math after your presentation, in front of you, and they tell you that they suspect they’re losing $40 million a year in botnet enabled fraud

You pull a number out of your ass and say “$150,000 a year, to start.” They say: “how soon can you deliver?”

This is the point where you start to get very excited.

Even before you start your company, a security company pays you $100k a year for access to a data feed produced by your technology

By some calculations, botnets are lodged in 17% of all computers in the world circa 2006, and this is only going to get worse. This is a massive, looming problem

You are also one of the first teams with cutting-edge, proprietary technology

So here are my questions:

- First, do you think this company has — at this point — discovered demand?

- Second, do you think this company will find product market fit?

- Third, do you think this company will result in a venture-scale outcome?

alas, the answer to all three questions is “no”

The name of this company was Damballa. It was founded by Merrick Furst and Matt Chanoff in 2006. It was sold for parts in 2016.

I should remind you that 10 years is a long time. Most careers last 40 years. 10 years is a quarter of that. Burning a quarter of your career on a startup with no real demand is a huge hit to take. I want you to really imagine this. If you start a company in your 20s, by the time you’re done, you’re in your 30s and you are married and are thinking about having kids (assuming you want them, and if you don’t have them already) … that, plus your parents are getting old. If you start a company in your 30s, by the time you’re done, you’re in your 40s, and if you have kids they take up a lot of your time and your parents are having serious health issues

And it’s not even that easy to tell that you are stuck in a dead end startup — as the Damballa case demonstrates, it is absolutely possible to be burning through all those years believing that you’re on the cusp of a breakthrough

Well, the good news is that the founders of Damballa spent the subsequent years puzzling over their decade-long experience. The result of their thinking and then experimentation was — first, Flashpoint, an incubator program at Georgia Tech with a remarkable track record

And, second, a set of ideas around demand that I believe are the first major contribution to the state of the art since the Jobs to be Done framework. These ideas were published as the book The Heart of Innovation in 2023.

Furst’s and Chanoff’s ideas happen to be the first thing I’ve seen that helps explain Vanguard. They call their approach ‘Deliberate Innovation’. The goal of Deliberate Innovation is to identify ‘authentic demand’ — that is, the kind of demand that means product-market fit

Situations, not Psychographics

The first big idea in Deliberate Innovation is about situations. (trigger?)

There’s this old, famous story about Ignaz Semmelweis, the Hungarian doctor who, in 1846, discovered that washing your hands with chlorine right before delivering babies would reduce the rate of childbed fever

admitted to a mental asylum when he was 47 years old. Semmelweis died just a few years later.

there’s also a way to read this as a story of demand. Two decades after Semmelweis passed, germ theory beat out the miasma theory as the prevailing theory of disease. As the theory took hold, it became unacceptable for doctors to not wash their hands before treating patients.

What changed? The answer is not customer pain, nor customer desire. The idea that doctors suddenly desired soap is not the right frame to use.

What changed was simply … default behaviour. (new status quo)

In human behaviour, there are actually many things that we do that do not readily fit into models of desire, or pain avoidance, or progress

Sometimes what we do depends not on what traits we have, but what situations demand of us.

1971 Stanford Prison Experiment

There are many problems with this experiment, but it continues to be cited when talking about the ‘situationist’ theory of human behaviour.

this isn’t just theoretical. Situation design is also useful in many real-world environments. Take, for instance, how a stage magician gets an audience member to participate in a magic trick.

chain of events, the magician creates a series of situations where the audience member cannot not do what the magician wants her to do.

So the first big idea in The Heart of Innovation is that situations matter as much if not more than psychographics or demographics when evaluating demand. Another way of putting this is that people buy based on the situation they find themselves in. (trigger)

The straightforward application of this is that if you’re doing sales, you should study the situations that people buy, and then find a way to hunt down or create more such situations. But this is not a novel idea. And — even if it was — existing frameworks already exist that help you when you’re identifying demand in the context of a sales motion.

Where Deliberate Innovation shines is that it extends this idea to the earliest stages of product creation

If you’re creating a new product, one that has never been sold before, then the recommendation is slightly different: demand hides in the situation.

We’ll talk about how they do that in a bit, but first we need to talk about one final, major idea that is actually the primary contribution of The Heart of Innovation.

The Not Not

We’ve just seen that Deliberate Innovation’s first idea is about situations: that situations can be as if not more important than customer traits when searching for demand.

Deliberate Innovation’s second idea is a razor that builds on this: a precisely crafted notion of what demand looks like. This idea is actually the more important one, because the ability to identify authentic demand tells you when you don’t have it. This allows you to avoid a Damballa-like outcome.

The razor is this: Authentic demand exists for a solution when someone is put in a situation and they cannot not buy (or use) the solution.

the job of the founder is to find a ‘not not’.

Why is this frame superior to the traditional method of evaluating demand?

The key lesson that Furst and Chanoff took from their Damballa experience is that evaluating demand in terms of value propositions, desires or pains is simply not predictive.

In truth, the following points are all observably true:

- Pain is not predictive because you and I have many pains that we don’t do anything about. We learn to cope. And so if we do not act on all our pains, then interviewing for pain is actually a crapshoot

- Desire is not predictive for the same reason.

- Innovation frameworks like ‘Lean Startup’ and the ‘Customer Development Model’ do not work reliably.

- all the existing demand frameworks (including the two that we’ve studied - JTBD and Sales Safari) assume that a purchase decision has already been made before you interview for pain. This is an entirely different situation from the one you find yourself in at the earliest stages of new product development.

there are companies that have tapped into authentic demand that do not solve any explicit pain. Facebook, Tiktok, and Instagram are good examples of this. For these companies, what you will find is that users with access to these apps cannot not reach for them when put in many, many situations. They have become habituated. Vanguard is also a good example of the same phenomenon, albeit with different dynamics. In all of these companies, it is more accurate to say that default behaviour changed in relation to a product

Vanguard succeeded because the consensus view on investing for retirement changed, and Vanguard benefited because it was waiting, perfectly positioned to receive that torrent of demand

Finally, decoupling demand from pain gives you more tools in your toolbox

For instance: demand can be influenced if you change the situation.

- ...if you get the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to mandate that all new drug applications must be submitted in a proprietary file format produced by your statistical software....

Demand is tricky! Anyone who has spent time building new products or startups feels the slipperiness of demand in their bones. This is why Eric Ries’s Lean Startup, and Steve Blank’s Four Steps to the Epiphany do not work consistently. This is why I argued that the Idea Maze is actually a useless idea, and why expertise research into entrepreneurs finds that repeat founders accept the skill of entrepreneurship as one of improvisation. Identifying and pinning down demand is the central problem of all new venture creation.

The ‘not not’ is the first attempt I’ve seen to conceptualise demand without resorting to the language of pain — the predominant model of demand since Ted Levitt’s 1983 book The Marketing Imagination. And it actually accomplishes a lot by doing so.

First, notice the double negative. The ‘not not’ is incoherent to think about — and this is by design. Why? Well, the biggest problem that founders have when validating their startup idea is that they are biased: they want their ideas to work

Framing authentic demand in terms of a ‘not not’ makes reasoning about demand slightly more incoherent, and therefore makes it marginally harder to perform this self deception.

Second, notice how the ‘not not’ formulation removes certain avenues you may use to lie to yourself.

using the ‘not not’ razor is more brutal: “nope, we haven’t found a situation in which people cannot not buy our solution. We think we should modify A, B, or C and try again. Should we give it another go?

A Better Definition of Product Market Fit

For years now, experienced founders and VCs have attempted to describe PMF in a variety of ways

The problem with all of these definitions is that they are imprecise. I am absolutely certain that experienced VCs and founders are able to identify PMF when they see it, but coming up with a universal razor that captures their felt sense is a lot harder than it seems

You can read a particularly noteworthy approach by serial entrepreneur Jason Cohen here — he attempts to document what PMF looks like by pairing anecdotes with observable data. ((2023-11-26) Cohen Product-Market Fit Experience Data)

But the not not gives us a better way of defining PMF. Put simply, you have PMF when you’ve found authentic demand.

*Why is this useful?

To founders, this is obvious: it is useful because it gives you clear guidance when you’ve found PMF*

ask: “is our prospective customer ok with not buying our solution?”. If the answer is no, you have PMF (contingent on finding more customers in situations like this); if the answer is yes, you do not.

For VCs, defining PMF in this way means that you have a method of picking startups who have found PMF just a bit before the adoption curve becomes clear to other investors

you could verify PMF qualitatively — months before signs of PMF shows up in a startup’s adoption curve

this is a limited advantage: if this essay is successful, it will result in the idea being more broadly known, meaning that more VCs are able to identify PMF at earlier stages.

This is, incidentally, why Furst’s and Chanoff’s Flashpoint incubator was so successful. I am not allowed to talk about their returns, but suffice to say I am quite impressed with their track record. The bit that I am allowed to talk about is that Flashpoint’s kill rate was extremely high. This meant that Furst and Chanoff were particularly good at killing startups that had not found authentic demand by the end of the program

I should also note that Furst and Chanoff are now semi-retired: both have had remarkable careers and have no need to continue running an incubator. Flashpoint no longer exists. Their ideas are now being carried forward through a successor program run by Erik Reinertsen and partners.)

it might actually be better to drop the use of the phrase ‘product market fit’ whilst you are actively searching for it. PMF describes a desirable end state, but is not precise enough to identify potential problems during the search for that state, or even potential problems that may occur shortly after finding the state. Instead, I recommend adopting the language of ‘authentic demand’, ‘not nots’ and ‘situations’.

Startup veterans know that it is possible to lose product market fit. As an example, startups that provided virtual event software like Hopin and Welcome exploded with demand during the Covid pandemic, as a result of lockdowns. They all lost PMF and died after Covid ended

With the language of authentic demand, though, it is easier to reason about when and how authentic demand can disappear

using the language of authentic demand allows us to identify when demand emerges over a long period of time. This is something that existing PMF discourse cannot handle. In the case of Vanguard, it took 15 years for index funds to reach large scale adoption. But authentic demand did exist in the early days, especially after John Bogle got rid of their load fees in 1981.

Of course, the upshot of all this is that authentic demand is still a bit of a negative art. Having the concept of authentic demand doesn’t actually help you find it; the search is still idiosyncratic

But it gives you two powerful things:

It tells you when you’ve found it.

And it prevents you from lying to yourself.

Solving the Vanguard Mystery

I think there are two questions that you should ask when faced with the Vanguard case

- First, was it possible to predict the eventual dominance of passive investing over active investing?

- Second (and this question is the more important one for founders): was it possible to identify authentic demand early in Vanguard’s life?

The answer to the first question is, I think, no. I do not believe it was possible to predict the absolute dominance of passive investing today. Passive’s growth took even Vanguard founder John Bogle by surprise

But on the second question, I think that: yes, it was entirely possible. That is: I think that if you were equipped with the ideas of Deliberate Innovation back in the 70s, it would’ve been possible to identify demand relatively early in Vanguard’s life. Possibly by the late 70s, but definitely by the early 80s.

One reason I believe this was that there were already situations in which index funds won, even before Vanguard had launched. But you would have to look carefully. An early one came from the pension funds of the Baby Bells.

In Trillions, Robin Wigglesworth’s book about the rise of passive investing, the contributions of these managers are described thus:

- studying how their swelling investment plans were faring in the early 1970s. “They found out that their active managers were basically swapping bananas. One part of the system would be selling IBM stock, and another part would be buying IBM stock at the same time.”

- Moreover, some pension executives began to slowly realize that many of the fund managers had hired were in reality little more than “closet indexers.” In other words, they essentially just mimicked the performance of the stock market as a whole, but charged fees as if they were engaged in an expensive hunt for the best securities

By the end of 1977, there was about $2.9 billion of pension fund money in the smattering of index strategies that had been launched. The 1974 bear market was a big impetus, but the longer-term picture slowly becoming clearer at the time was also grim. AG Becker, a prominent finance industry consultancy, found that 77% of US pension managers had trailed behind the S&P 500 in the decade ending December 1974.

When I told Furst about this story, I asked him if we could be more concrete about the types of not nots he’d seen. He told me that there were a few that came up repeatedly:

- Physical or logical impossibility (think about attempting to submit to the FDA clinical trial data in a format other than the mandated standard).

- Social unacceptability

- Value system violation

- Habituation (perhaps due to exposure to a secondary reinforcer)

- and psychological paralysis (if consumers find alternative actions uncomfortable or incoherent, they would take a ‘default’, psychologically comfortable path).

We can do a slightly better job of explaining Vanguard’s success through this language: in the initial years, indexing’s adoption resulted from a value systems violation. Pension fund managers noticed that many of the actively-managed funds they invested in delivered a subpar return for excess fees. Exposed to this knowledge (and with more potent arguments slowly trickling out from academia), they could not not switch certain allocations to passive, because they acted as fiduciaries for their pensioners.

Retirement savings had to be invested somewhere, and as active investing of various types became more and more socially unacceptable to retail, all of that money started going to index funds.

Furst warned me that it was not necessary to categorise the not nots. As a founder, you care that a not not exists, not that a not not ‘belongs’ to one category or another.

it is more productive to just reason about the sorts of behaviours that emerges in a particular situation. What pushes people towards or away from certain behaviours? Why? A typology does not help you much with this approach; being curious about the situation is more important. (curiosity)

Furst also said that he didn’t like this sort of slow-growing demand — at least for venture-backed startups

The venture model is not well-positioned for long-term compounding bets. Thankfully, John Bogle had no such constraints.

How To Find Authentic Demand?

Those of you who have read Commoncog for some time would know that I have a track record of taking ideas I’ve read and putting them to practice.

So please believe me when I tell you that the process Furst and Chanoff describes in their book is impossible to put to practice from just reading alone. This is the sort of thing that will require apprenticeship from someone who has done it before, or at least a year of serious trial and error.

That said, I think there are three, easy-to-use ideas here:

- Furst told me that if nothing else, one thing you can put to practice immediately is to ask your prospective customers: “Hey, I’m thinking of making this thing. Would it be ok if I don’t make it? Would it be possible for you not to buy?”

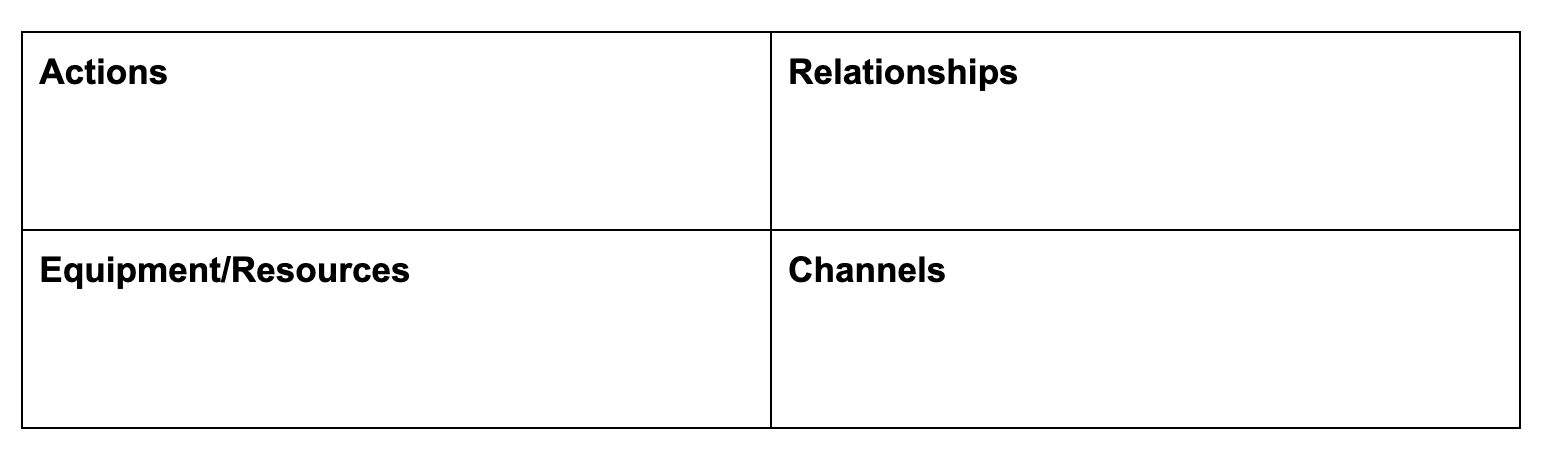

- One of the methods that Furst and Chanoff teaches is a thing called a ‘situation diagram’. I believe this diagram can be put to practice easily, and may be adapted for other go-to-market research motions.

- I think the basic ideas of Deliberate Innovation — as presented in this essay — are potent enough that you could probably integrate them into your own work. This is especially true if you currently have experience with demand. If you do, it shouldn’t be too hard to come up with your own unique methods; the razor by itself is a huge help.

But let’s get down to it.

When you're hunting for demand, you need a way to document the situations that you find. These include situations that your prospective customers are in, but also situations that include other stakeholders

*How do you record this? Well, you record it using a Situation Diagram.

A Situation Diagram looks like this:*

The four boxes represent the four parts of a situation that an observer can see and test:

- Actions: people doing things.

- Equipment/Resources: products and services used in the performance of actions.

- Relationships: activities by people other than the person whose actions we’re looking at, serving as a resource for those actions

- Channels: pathways by which equipment or other people’s actions reach and impact the situation.

As an example, a situation diagram for a doctor breaching the sterile field during a surgery might be: (see diagram)

Let’s pretend that you are a founder who wants to introduce a new device into the operating theatre. The right stance to take when creating this situation diagram is to regard this is ‘business as usual’ — all the elements of the situation are working together to help the various actors cope with their various tasks; you are not yet a factor. You can only insert yourself (and your proposed solution) if there is a gap in the situation: some … thing that actors are currently not coping as well as they could be. The closing of this gap generates a ‘not not’.

The authors write (all bold emphasis mine):

Diagramming situations clarifies how authentic demand arises from within them and how the components of those situations stick together. People in situations cope with them so that the situation remains in place; when gaps open, they act to fill them

The authentic demand is for the gap to be closed and the situation maintained, but it’s expressed by the customer as demand for the object, the piece of paper.

Thinking of the demand as being for the object itself obscures both the size of the market and the risk that the gap may be closed in some other way that wouldn’t be noticed as competitive until it’s too late.

Focusing on the gap forces you to grapple with “how many situations does this gap appear in?” This gives you a sense of the size of the market.

Focusing on the gap also forces you to ask: “what other ways might people use to close the gap?” Those alternatives may compromise the demand for your proposed product or solution.

So for instance, if you want to introduce an AI-driven camera system that will alert the doctor when they breach the sterile field (e.g. when they touch their ear), the obvious counter would be that “I can just ask my scrub nurse to warn me; they are already there, and they are already trained to do this.”

I will admit that I’m not completely pleased with this language around gaps. I am not certain I could recognise a gap if I found one; the way gaps lead to ‘not nots’ feels slippery to me.

For instance, some gaps are created by the introduction of new information into a situation

In other situations, gaps are invisible because existing actors are coping decently, with whatever resources they have available to them. But if you introduce a solution that causes them to cope better, the actor will move to the new solution, and quickly

Given how slippery gaps are, perhaps you can see why it’s critical to do accurate situational bookkeeping

At Flashpoint, founding teams fill in a small mountain of situation diagrams as they conduct interviews with various stakeholders

In many cases, authentic demand reveals itself in an adjacent situation, not one that involves the initial customer you were targeting.

But … how should you conduct such interviews?

Documented Primary Interactions (DPI) (customer interview)

Flashpoint startups do anywhere between 200 to 400 DPIs over a three to six month period during their search for authentic demand. Founding teams typically start small, and build up to 20 or more DPIs per week.

Documentation includes documenting the design of the DPI as an experiment beforehand and recording what actually happens

Conducted with people involved in the situation of interest, as distinct from experts or other outsiders opining about a situation they aren’t directly party to. Primaries are people who are actually in situations. Secondaries are people talking about how other people they know or work with operate. Tertiaries are research reports or survey results. DPIs care only about primaries.

Constructed as an interaction intended to bring out a response that may reveal a non-indifference. This often involves doing or saying something that breaches a norm, in order to test whether or not the person is really indifferent to the change.

Unlike many interviewing methods, DPIs focus on concrete behaviours and circumstances, not motivations or outcomes. Also unlike other interviewing methods, investigators are expected to pre-register their views before starting a DPI session. These views look like: “What do I expect to find, and what do I expect people to do in a particular situation? What if I change something?”

As time passes, and you develop hypotheses for gaps that you might be able to insert yourself into, you begin to probe stakeholders with questions or experiments in order to uncover ‘nonindifference’.

If you’re lucky enough to identify a gap, investigators may start building small prototypes for actors in specific situations.

All of this is deliberate, time-consuming, and extremely difficult to do.

What is difficult is the tendency for founders to lie to themselves.

Furst and Chanoff outline the various cultural and psychological prostheses they had to build into the Flashpoint program in order to enable such truth-seeking behaviours

- Practice ‘unconditional positive regard’ — Everyone in the program is expected to show complete support and acceptance of a person no matter what that person says

- The use of Radical Candor — A lot of the work in Deliberate Innovation is noticing and then highlighting one other’s blind spots... but make it a point to practice this only in the context of unconditional positive regard.

- Attend to process, and the process cadence: focus on the inputs to the process. This is a weekly cadence of, first, planning activities and DPI exercises, then executing those DPIs, then debriefing, presenting and supporting each other as the results come in, and then prepping for the next week’s cycle. This shifts the focus to inputs (which founding teams have control over)

- Pay attention to indifference: Indifference is everywhere you look, once you learn to see it: most people in most situations don’t care about you or your solution. Becoming sensitive to indifference during the DPI process makes teams more aware of nonindifference when they finally find it.

If you want to put these ideas to practice, I highly recommend buying a copy for yourself, and then reading the chapters in Part 2 very carefully

Wrapping Up

The title of this essay reads “why most startups fail”. The implication, of course, is that startups fail when they don’t find authentic demand. Is this true?

There’s a paragraph, fairly early on in The Heart of Innovation, where Furst and Chanoff write (bold emphasis mine):

The biggest problem when creating a new form is being stuck in the world of ghosts. You and your innovation are not being drawn into the world. As smart, energetic, and diligent as you may be, the hard truth is that it’s not up to you to be welcomed; other people have to do it.

The ghostly reality sets in. People are already coping with their lives: customers are already buying something else, collaborators are collaborating, and investors are investing elsewhere. Your innovation is met with overwhelming indifference

they just keep adding to the to-do list until they run out of time or money or energy, at which point they abandon the innovation and come up with an excuse (usually something about market timing).

The biggest form of failure in startups is not finding authentic demand. Because, really ... what else could it possibly be?

Edited: | Tweet this! | Search Twitter for discussion

Made with flux.garden

Made with flux.garden